It's no secret that the blueberries crop has skyrocketed around the world, and the United States is no exception. In 2019, the most recent data available from the USDA's National Agricultural Statistics Service, 41,500 hectares were harvested in the United States, up 15% in just one year. Production used totalled more than 300,000 tonnes, jumping 21% from 2018, showing at least in part how much more efficient growers are becoming with improved varieties. In 2009, the total area was just 26,000 hectares, meaning that in just one decade, the area harvested in the US has increased by 60%.

Of the total used production in 2019, the quantities destined for the fresh market and processing were quite similar: 170,000 tonnes (57%) for the fresh market and 136,000 tonnes (43%) for processing. But prices were very different, with fresh market berries fetching four times as much: Eur 3.70/kg (USD 2.03 per pound), compared to a price for the processing product of only Eur 0.90/kg (USD 0.50 per pound).

With such an obvious incentive to grow for the fresh market, it's no surprise that growers who have traditionally grown for processing are increasingly looking to grow for the fresh market, says Lisa DeVetter, associate professor at Washington State University, Berry Crops. But one obvious problem is that growing for the fresh market obviously requires higher quality fruit, and has traditionally been hand-picked.

In the Pacific Northwest, where the harvest has boomed in recent years, this would mean an extraordinary effort. Even then, with the decline in available farm labour in the Pacific Northwest - just as growers feel elsewhere - it would be difficult. "If you had to hand-pick all that (fresh market) fruit," she says, "you would struggle to do it."

THE AGE OF AUTOMATION

If there are not enough hands, it means that you have to harvest by machine, and the share of growers who harvest blueberries by machine for the fresh market continues to grow.

"It's increasing rapidly," says DeVetter. "It was 10-20% about 20 years ago. Then, when labour costs started to rise, growers got motivated. In 2016, about 33% of fresh market fruit was machine-picked, according to national surveys.

IN THIS TIME OF COVID THE MECHANICAL HARVESTING OF BLUEBERRY COULD APPROACH 40-50% OF THE PRODUCT FOR THE FRESH MARKET.

Lisa DeVetter Associate Professor, Washington State University

"The share of blueberries mechanically harvested for the fresh market will be much higher by 2025".

This huge growth has come about because of improvements in harvesting machines that make it possible to harvest quality product for the fresh market, a movement that had a new vitality in 2013, he says. The following year, University of Georgia engineering professor Charlie Li, a sensor technology expert launched a USDA specialty crop research initiative. Oxbo International Corp. of Lynden, WA, which manufactures mechanical harvesters for a variety of crops, was involved in the project from the beginning, says Kathryn Van Weerdhuizen, Global Market Manager, Fruit at Oxbo Corp.

"The key to the project was the Berry Impact Recording Device (BIRD)," says Kathryn Van Weerdhuizen. The size of a blueberry, the BIRD could go through the harvesting process and help researchers understand the exact force that blueberries encounters.

"We could then determine a G-force safety zone for blueberries. The first fall is the worst because the fruit falls from the plant to the picker. It is a key step where the berry can bruise," he says.

Unfortunately, that height turned out to be rather small. The G-force experienced by a blueberry dropped on a hard surface results in adent once the height exceeds 30 centimetres, and blueberry plants can be 180 cm high. The machines have gone through several generations, he says, and researchers have tried all kinds of surfaces in search of the right material. In 2018, the second generation of machines was developed. These first soft-surface machines used neoprene, which worked well but was too susceptible to wear and tear.

"The problem was to find a material for the backing plate, which until then was made of Lexan, that was soft enough but also resisted wear and tear," Van Weerdhuizen says of all the lab tests. "People have tried to glue all kinds of soft surfaces onto hard surfaces, but it didn't work."

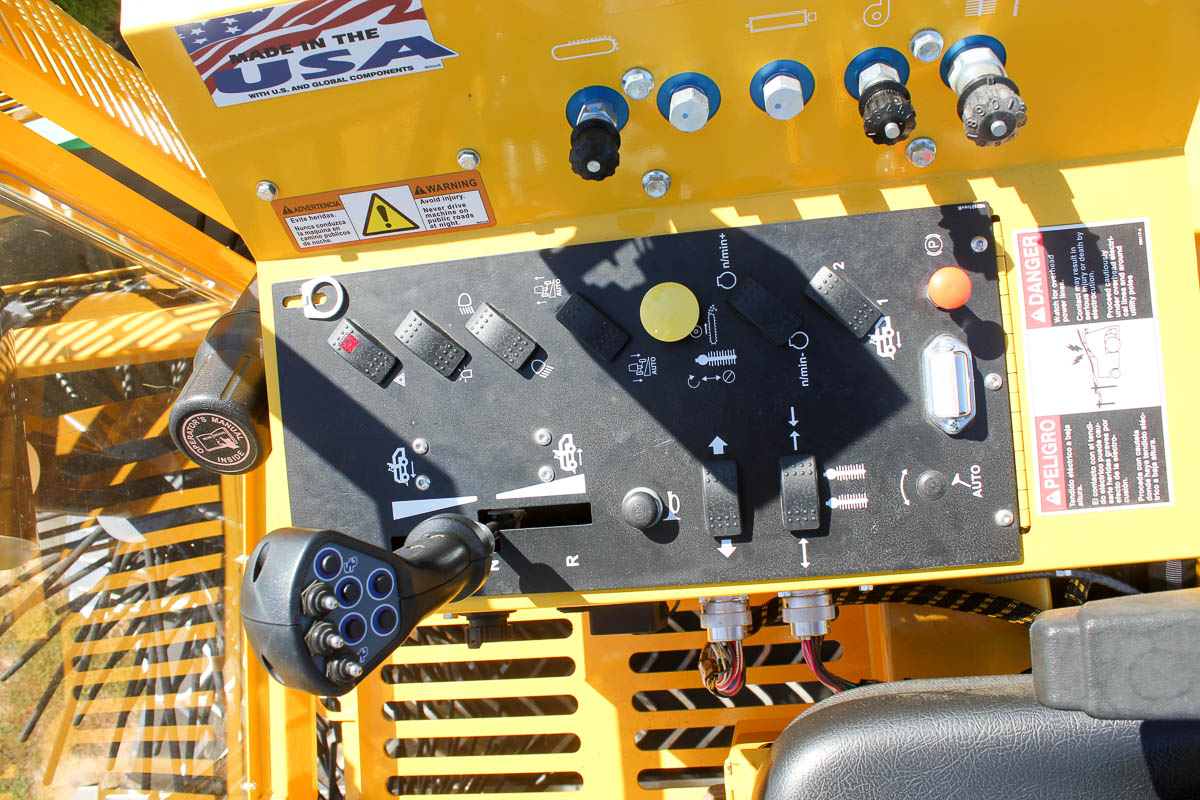

The Oxbo 7440 harvester is equipped with SoftSurface, which comprises pick-up plates modified with a food-safe elastomeric polymer and soft intermediate pick-up frames suspended above the pick-up plates and conveyor belts.

THE OXBO 7440 MECHANICAL HARVESTER

IN-HOUSE TESTS

In 2019, Oxbo took to the field to test the third generation of soft surfaces on two units, the 7440, a top-loaded model, and the 8040, a rear-loaded unit. They followed the harvest that year, starting in Florida, then moving up the coast to New Jersey. Then they tried soft-surface units on the west coast.

"Using them in the field and laboratory research are two different things, and even the third generation was not perfect," he says.

But the fourth generation that came out just last year has proven to be a game changer, says Van Weerdhuizen. Oxbo is using a food-grade elastomeric polymer - he says he can't be more specific about the material because it's patent pending - that is integral to the pick-up plate and a long suspended panel that absorbs the first, fundamental impact with the berries. Last year they sold four units equipped with the new set-up.

"We and customers have been impressed by the durability of the material," he says, "which can be replaced if you switch from fresh fruit to harvested fruit for processing."

THE OXBO 8040 MECHANICAL HARVESTER

Talking to these customers, however, proved difficult. All growers contacted for this article refused to speak on the subject, a fact that surprised neither DeVetter nor Van Weerdhuizen. "People who harvest by machine for the fresh market don't talk about it publicly," says Van Weerdhuizen. "There may be a bias among fruit traders - they put their own brand on the product - and they want to make sure it is of high quality."

There is also the fact that some packers have been getting poor quality fruit that has been machine harvested because some growers are not doing it right.

"So if the farmers who are doing it right have secrets and don't want to share what they are doing," he says. "There are a lot of good farmers who have invested capital and effort in what they are doing, and they have knowledge that as good entrepreneurs they don't want to make public," he says. "You have to, for example, maintain the cold chain, which requires putting together a lot of expertise to really do a good job."

A PRODUCER'S POINT OF VIEW

One grower agreed to comment, but only in writing and under guarantee of anonymity. He states that his company has been using the Oxbo harvester with SoftSurface for one season.

"Until now, we believed that machine harvesting for fresh was not yet a viable form of large-scale fresh harvesting," he writes. "We place a lot of value on quality and saw too many dents on traditional harvesters. However, when we tested the Oxbo with the SoftSurface installed, the overall quality changed dramatically. Heavy dents were halved, which in itself was a game changer, but light dents on the remaining fruit were also eliminated."

The grower continues: "Often when harvesting by machine, there are bruised berries that are very soft, which is easy to separate, and the remaining berries might be mostly firm but a bit soft. This new configuration helped to make the remaining berries as firm as the hand-picked ones. However, this did not solve all the problems overnight. Machine harvesting for fresh requires good harvesting timing, correct temperatures at harvest and the correct operating speed of the machine, which differs by variety. That is why we have chosen to immerse ourselves in this form of harvesting and to make sure that every kilo we carry is of at least as good a quality as that harvested by hand.

"Sometimes, it is even better than hand harvesting because you can harvest when the temperature is lower than a traditional hand harvest. However, this configuration has some disadvantages. The material can be punctured relatively easily, and it is expensive to replace it after it has been punctured. In addition, it seems that many of the new generation materials will have to be replaced every year. On the whole, however, we believe that with proper handling, quality should not suffer with the new harvester model. But it can be risky to take the plunge without doing serious research first".

Van Weerdhuizen says the grower has hit the nail on the head. "I cannot say that in general machine harvesting of fresh fruit for the market poses no problem," he says. "We think producers need to understand that it is a complete process. There is no easy, turnkey solution for harvesting blueberries, especially for the fresh market. That is why people are so cautious. Everyone wants the fresh market price for their fruit, but there is an art to machine harvesting that needs to be mastered. Will machine picking ever be as good as hand picking? Yes, I think so, but it won't just be about improvements to the machine, but genetics, pruning, etc."