Exceprt from “Repensando el mercado del arándano: Estrategias para el resurgimiento argentino” by Facundo Delgado

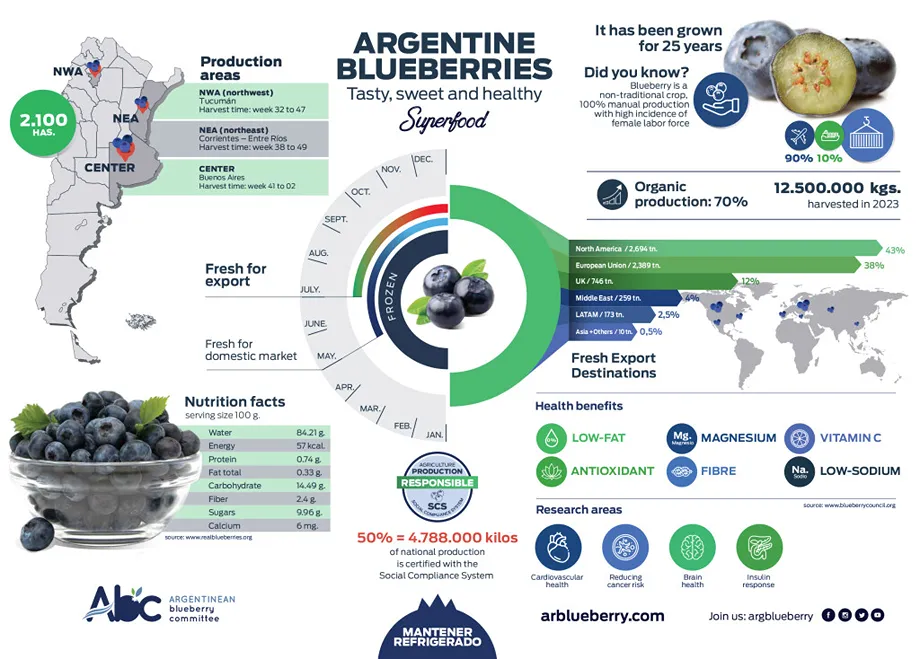

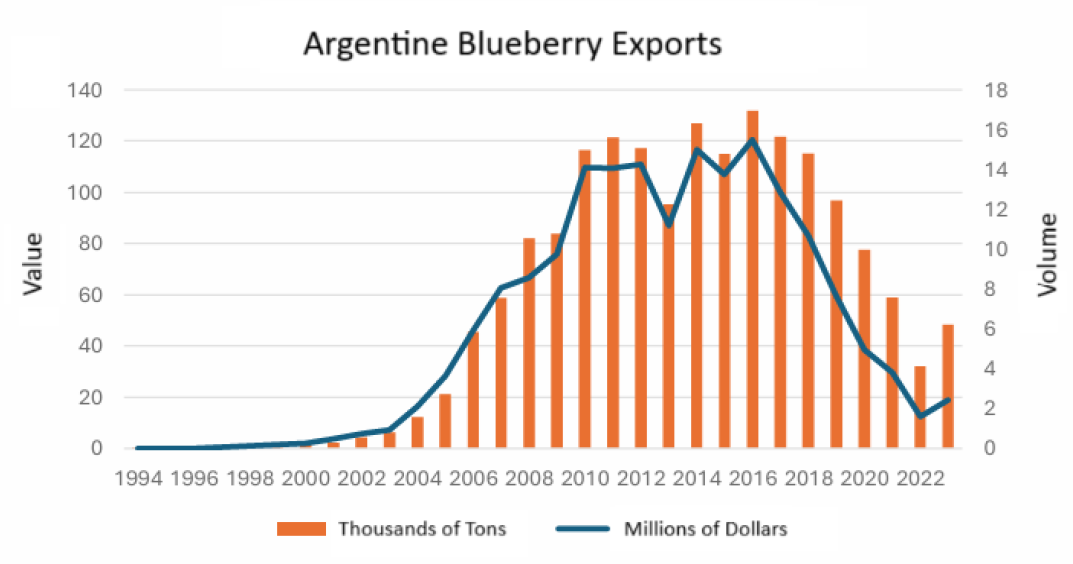

Over the past twenty years, Argentina has gone from being a leading player in the global fresh blueberry market to occupying a marginal role. In 2016 the country reached its peak, with over 4,200 hectares cultivated and nearly 120 million dollars in exports. Today, however, cultivated area has fallen by 35% and exports have dropped by more than 60%.

This negative trajectory contrasts with the continued expansion of global demand, driven by health-conscious consumption, rising disposable income, and the growth of European, North American and Asian markets. The aim of this contribution is to analyze the causes of Argentina’s decline and to propose concrete strategies for reversing the trend.

A Growing Global Market

World demand for fresh blueberries has grown exponentially: from around 27,000 tons in 1990 to over 700,000 in 2020, with forecasts surpassing one million tons by 2030. The United States, the Netherlands and Germany remain the main importers, but emerging markets such as China and India are showing annual growth rates above 15%. For South America, seasonality has represented a unique opportunity: producing between September and March, when northern hemisphere supply is scarce and prices peak.

Argentina seized this opportunity in the early 2000s, reaching a stable volume of about 15,000 tons per year between 2010 and 2016. However, that record year also marked the beginning of a decline that continues to this day. In the meantime, Peru multiplied its cultivated area tenfold, while Chile consolidated its logistical leadership.

Argentina’s Structural Challenges

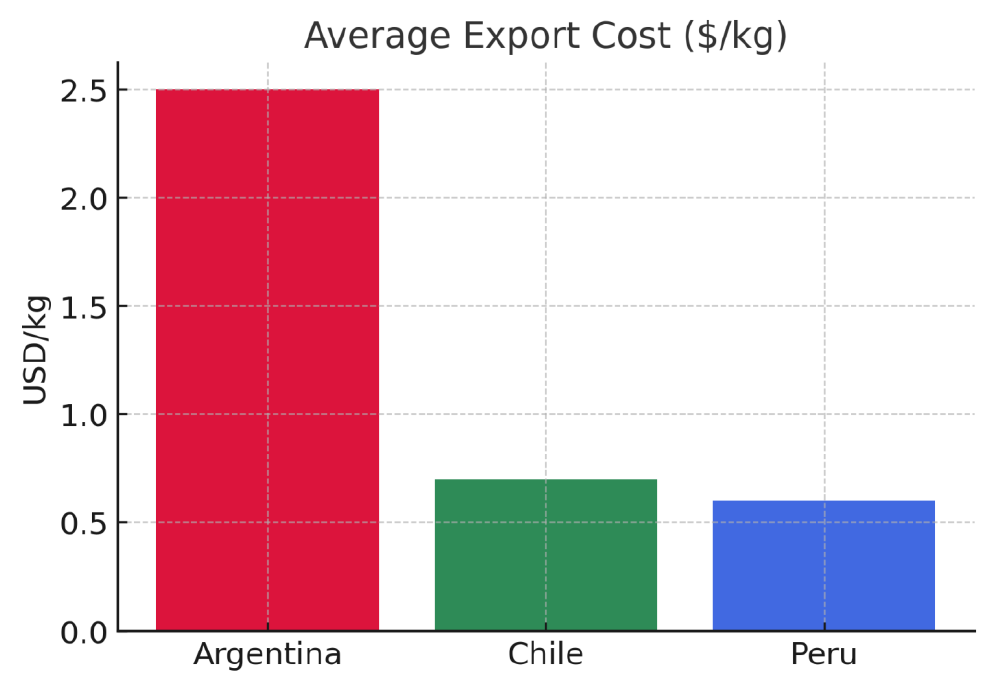

Three main factors explain Argentina’s loss of competitiveness: export costs, the lack of free trade agreements, and limited production scale. Export logistics costs are among the highest in the world: between 40% and 50% of the international blueberry price, compared to less than 15% for Chile and Peru. This is because the country relies almost exclusively on air freight, at an average cost of $2.5 per kilo, while competitors can use sea transport for less than $0.8 per kilo.

In Argentina, in fact, shipping by sea is limited by the rapid deterioration of blueberries during long ocean crossings, which reduces their commercial quality.

Another key factor is trade policy. Chile and Peru benefit from Free Trade Agreements with the United States and the European Union, their main markets. As a result, they export tariff-free, while Argentina faces duties that drastically reduce margins. Moreover, the average Argentine producer manages about 25 hectares, compared to the hundreds or thousands of hectares of Peruvian giants such as Camposol or Hortifrut. High energy and labor costs, coupled with limited access to credit, further aggravate the situation.

Lessons from Peru and Chile

The Peruvian model rests on three pillars: large-scale expansion (over 35,000 hectares), vertical integration, and genetic innovation. Companies control every stage, from varietal research to retail distribution in international supermarkets. This ensures punctual deliveries and high-quality fruit, with less than 10% of shipments facing complaints. In addition, Peru has successfully attracted foreign investment, which has accelerated its growth.

Chile, while not expanding at Peru’s pace, has maintained a stable output of over 100 million kilos per year, thanks to its logistical expertise, trade agreements and varietal diversification. Argentina, in contrast, has seen its global market share shrink from 6% to less than 1%. The Chilean experience shows how institutional stability and international credibility can be as decisive as technology.

Strategies for Argentina’s Comeback

Interviews with producers highlight four priority areas: building cooperatives and consortia to leverage economies of scale; diversifying varieties to extend the harvest window; adopting agronomic innovations such as micropropagation to reduce costs; and negotiating new logistics routes while targeting alternative markets in Asia and the Middle East.

Another strategy is partial vertical integration, at least up to packaging and transport, in order to reduce intermediaries. This requires targeted financing and policy support, but can improve profitability for medium-sized producers. Pilot experiences in Tucumán and Entre Ríos show how consortia can increase the feasibility of shipping by sea through innovative refrigeration systems.

Voices from the Field: Testimonies from Argentine Producers

Interviews conducted with producers from three strategic regions—Concordia (Entre Ríos), Tucumán, and El Bolsón (Río Negro)—revealed shared challenges and diverse approaches to blueberry production and export.

A producer from Concordia emphasized the burden of domestic logistics costs: “The problem isn’t just air freight—Argentina lacks a productive railway infrastructure. Moving goods within the country is already too expensive.” He also pointed out the impact of energy costs: “Electricity for irrigation is a major expense, especially in the warmer regions.”

Another interviewee, active in the province of Tucumán, spoke about the importance of genetic autonomy: “Designing your own plants is essential. Otherwise, every planting cycle means paying royalties to big companies.”

Conclusion

Reviving Argentina’s blueberry industry depends not only on agricultural factors but on a structural transformation that combines innovation, cooperation and public policies. Without such changes, the country risks consolidating its marginality.

With a strategic, long-term approach, however, Argentina can regain relevance, contributing to export diversification and the sustainability of regional economies.

Facundo Delgado (Master’s Degree in Economics – University of Buenos Aires) facudelgadocah@gmail.com